|

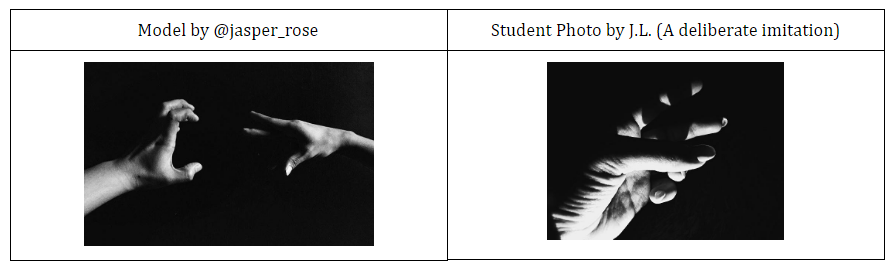

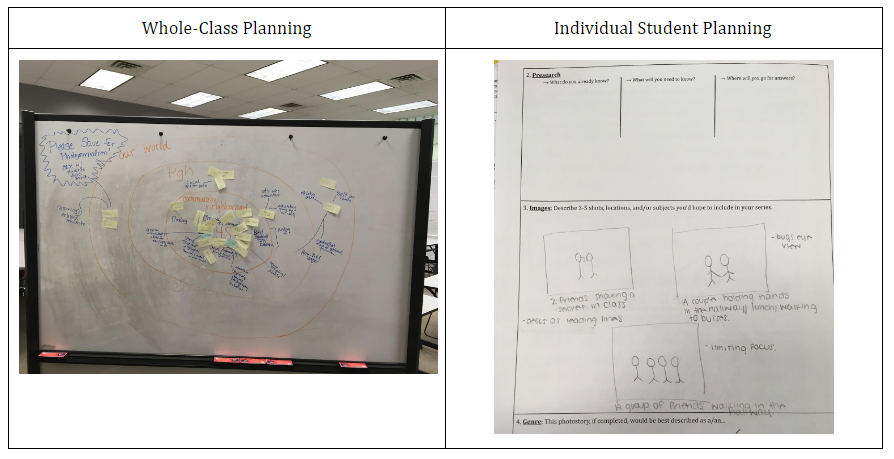

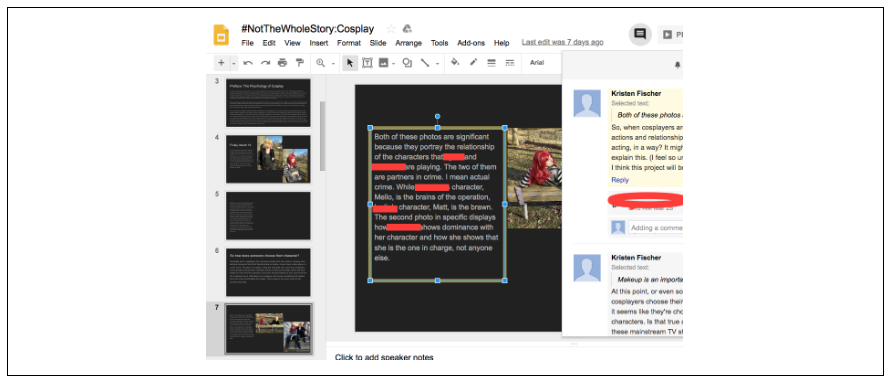

This is the latest in a series of blogs from the teacher cohort. - By Kristen Fischer “Easy reading is damn hard writing,” noted Nathaniel Hawthorne, and I have to agree. Whether one is writing with images, with words, or multimodally, writing well is not easy. Technology is rapidly contributing to new genres of communication; yet, as most teachers and students can attest to, the language arts classroom hasn’t changed much since the days in which perhaps a pencil was considered technology. Resources, training, time, philosophies, and fears contribute to the stagnancy, and the focus remains on the study of traditional texts, with occasional editorial cartoons thrown in. I count myself as guilty. An added concern: We know it isn’t enough to simply study and consume texts and that our students must also produce them. Thus, if we struggle to integrate the study of multimodal texts into our classrooms, it is no wonder we struggle to integrate opportunities to compose them. Our Fluency Project readings and conversations have foregrounded student voice and student empowerment, and surely to prioritize both means to teach our students to be creators of meaningful new media. This is undoubtedly challenging to do in a traditional English class, though I’ve had a few successes (one being the modern-day witch hunts infographic project in conjunction with Miller’s The Crucible, which I generated during the first summer weeks of The Fluency Project). My photojournalism elective, however, has presented an opportunity for me to foreground multimodal composing, and for the past 12 weeks, students have engaged in a variety of small challenges and a few larger “photo essay” projects. In this class, students aren’t “just” taking pictures. The focus on images doesn’t preclude the possibility of rigor. The photo essay assignments in particular--as I’ve framed them--have required students to brainstorm, conduct research, and construct arguments that rely on both words and images. Consequently, I’ve observed Hawthorne’s remark to be just as true when writing with pictures as it is when writing with words; either way, “Easy reading is damn hard writing.” In addition to affirming that there’s always potential for rigor in composition assignments, regardless of the medium, here’s some other reflections from my immersion into the world of teaching multimodal compositions: 1. Never underestimate the importance of model texts: I realized this when we discussed captions. Students have read captions, but they aren’t sure of what to do when tasked with writing them. Students must scrutinize the dynamic between words and images to understand the role each is playing; in a multimodal photo essay, the pictures don’t simply reiterate the words, or vice-versa. Each adds something the other is less adept at communicating. 2. Just because a picture can be snapped in a fraction of a second doesn’t mean visual composing is quicker or easier than verbal composing: Sure, my students have taken many snapshots, but only a handful of them have been any good. Most quality shots, they’ve learned, are the result of planning, persistence, skill, resources, or a combination of those factors and more. At the end of a project, I usually require a reflection on their best shot. The experience of reflecting on how a compelling shot or argument came about affirms to students that most effective communication is the result of deliberate planning. I’m confident the students who composed the essays on weightlifting and tattoos would confirm they required a lot of revision and numerous hours to compose. 3. It’s going to take longer than you think: I have years of notes by now on how long it takes for me to guide students through the personal essay and the research project; I have notes on the challenges we will experience with resume templates and works cited pages. When it came to these projects, however, I underestimated the time students would need to produce their essays by about 5-7 days. Most of our additional time was spent on the brainstorming at the start and on the polishing at the end, but it’s also important to account for the—wait for it—inevitable technology hiccups. 4. The product may be different, but the struggles will be similar: The student who struggles with generating a topic will still struggle with generating a topic. The student who doesn’t proofread well will still not proofread well. The student who needs the assignment chunked will still need the assignment chunked. Most students will feel frustrated and relieved at various points. The process of composing verbally isn’t that different than the process of composing visually: planning, arranging, polishing... these happen in both. 5. Yes, you can grade this, and yes, I still teach writing: I’ve read articles and blog posts that celebrate the promise of multimodal assignments, yet bemoan the difficulties of assessing such non-traditional products. I’ve also read plenty that fear the integration of images means the death of the written word in classrooms. But if I make the rubric and the assignment, I decide what to require and how to measure its quality. I can choose to prioritize writing quality even though photos happen to be a part of the assignment by choosing to grade the media-rich components for completion and the writing more heavily--or vice versa. I can promote quality in written expression by grading reflections and proposals for organization, detail, clarity, and conventions, while still inviting creative and effective multimodal communication. As long as I’m transparent and clear with the students about our objectives and criteria, I can weigh elements in a variety of ways. Communicating well is for most people a challenging task; the cognitive demands are high, and a conscientious composer is constantly debating how to best accomplish a goal, given an audience. Just because the medium is images doesn’t mean the rigor has been lost. Sure, writing a verbal essay is different than writing a visual one, but instructors can creative multimodal assignments that value features shared by both and that challenge students to practice skills relevant to multiple avenues of communication.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed